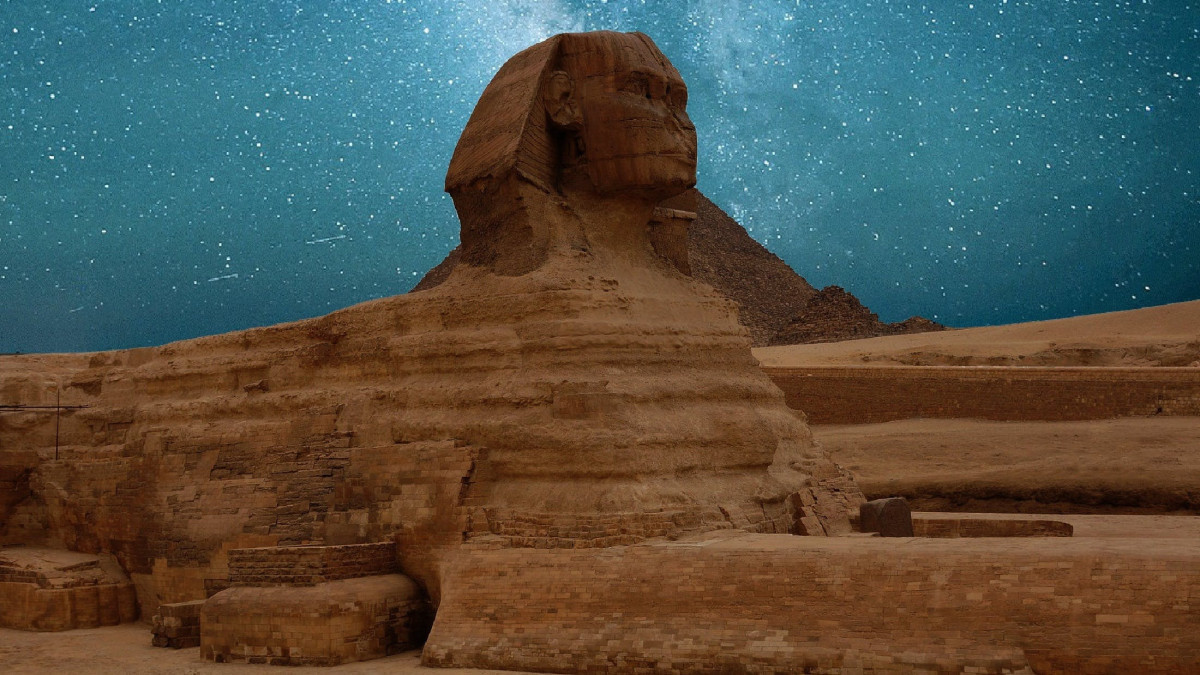

Scientists offer evidence to support possible Great Sphinx origin story

EL.KZ Информационно-познавательный портал

More than 40 years ago, Farouk El-Baz — a space scientist and geologist known for his field investigations in deserts around the world — theorized that the wind played a big hand in shaping the Great Sphinx of Giza before the ancient Egyptians added surface details to the landmark sculpture, El.kz cites CNN.

Now, a new study offers evidence to suggest that theory might be plausible, according to a news release from New York University

Now, a new study offers evidence to suggest that theory might be plausible, according to a news release from New York University.

A team of scientists in NYU’s Applied Mathematics Laboratory set out to address the theory by replicating the conditions of the landscape about 4,500 years ago — when the limestone statue was likely built — and conduct tests to see how wind manipulated rock formations.

“Our findings offer a possible ‘origin story’ for how Sphinx-like formations can come about from erosion,” said senior study author Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, in a news release. “Our laboratory experiments showed that surprisingly Sphinx-like shapes can, in fact, come from materials being eroded by fast flows.”

The team behind the study, which the release said had been accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Fluids, created clay-model yardangs — a natural landform of compact sand that occurs from the wind in exposed desert regions — and washed the formations with a fast stream of water to represent the wind.

Based on the composition of the Great Sphinx, the team used harder, non-erodible inclusions within the featureless soft-clay mound, and with the flow from the water tunnel, the researchers found a lion form had begun to take shape.

Within the desert, there are yardangs that exist that naturally look like seated or lying animals with raised heads, Ristroph told CNN. “Some of them look so much like a seated lion, or a seated cat, that they’re sometimes called Mud Lions. … Our experiments could add to the understanding of how these yardangs form,” he said.